After six books of photography and writing, Wheeler Antabanez has carved out a niche for himself as a career trespasser. One thing his cult following can expect to find in his books is the exploration of hard-to-reach, abandoned, and often dangerous places. There is a thrill surrounding his new releases – where has the 47-year-old dared to go next?

“It’s a thrill for me, too,” Antabanez said.

His latest book, Wheeleroidz, is no exception, a collection of Polaroids that once again shows readers places across North Jersey that they didn’t know about or were too fearful to go.

Dressed in all black, with black-laquered nails and tinted sunglasses, Antabanez arrives at the abandoned bank on Claremont Street in Montclair, which is one of the places he photographed in his latest book of Polaroids. His real name is Matt Kent. Antabanez is his disaffected alter-ego.

As we sat in the shade underneath the shuttered bank’s perennially closed drive-up window, we discussed his nonfiction, his recent foray into novel writing, his criminally underrated works on Weird New Jersey, and the genius of the late British underground rapper MF Doom.

The editors of Weird N.J. once called him an evolved “anti-hero” in the preface to “Nightshade on the Passaic,” a searing work of gonzo journalism that garnered Antabanez a special edition in the magazine in 2008.

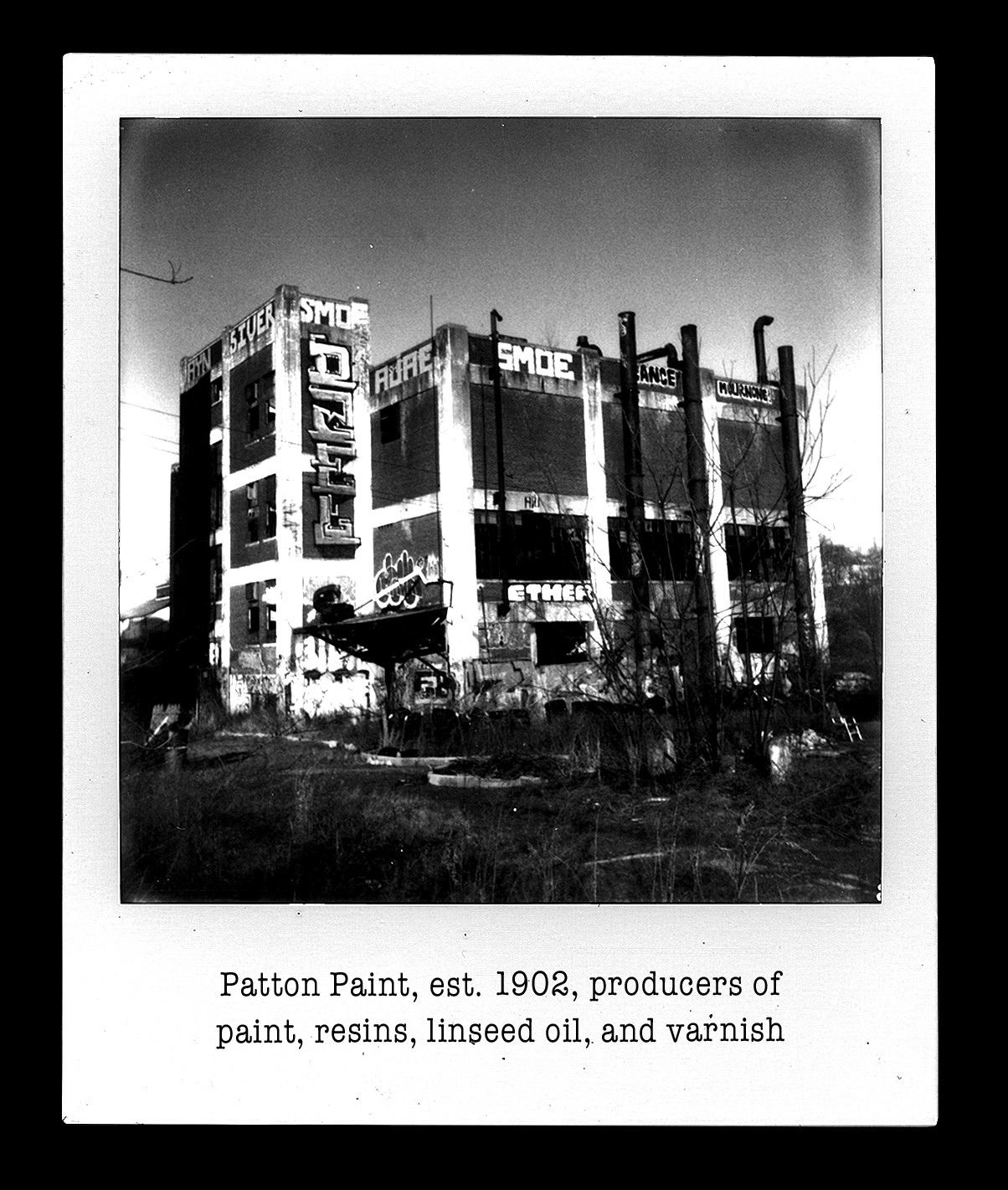

“We’ve known him as an explorer of abandoned locations, where he finds beauty in the bleak contrast of death, decay, and the human drama that once played out in such places,” the introduction reads. The description still rings true in his latest endeavor.

Antabanez often launches a new creative project as a way to deal with inner restlessness. The idea for Wheeler’s last book – Walking the Boonton Line, which this publication covered in 2021 – dealt with the isolation of the pandemic quarantine and the grief of losing a loved one. The book was a huge hit, featured in the Star-Ledger and WFMU, and tapped into our collective world-weariness brought on by COVID-19, while riding the anticipation for the Essex-Hudson Greenway, which will convert the abandoned Boonton line tracks into a linear park.

This undertaking was no different – it came at a time when the author needed to heal, physically this time, from spinal surgery.

“I couldn’t lift my arm,” said Antabanez as he demonstrated his limited range of motion by raising his tattooed elbow. “The only thing I could do when I was injured was write – I would prop myself up with pillows and just write.”

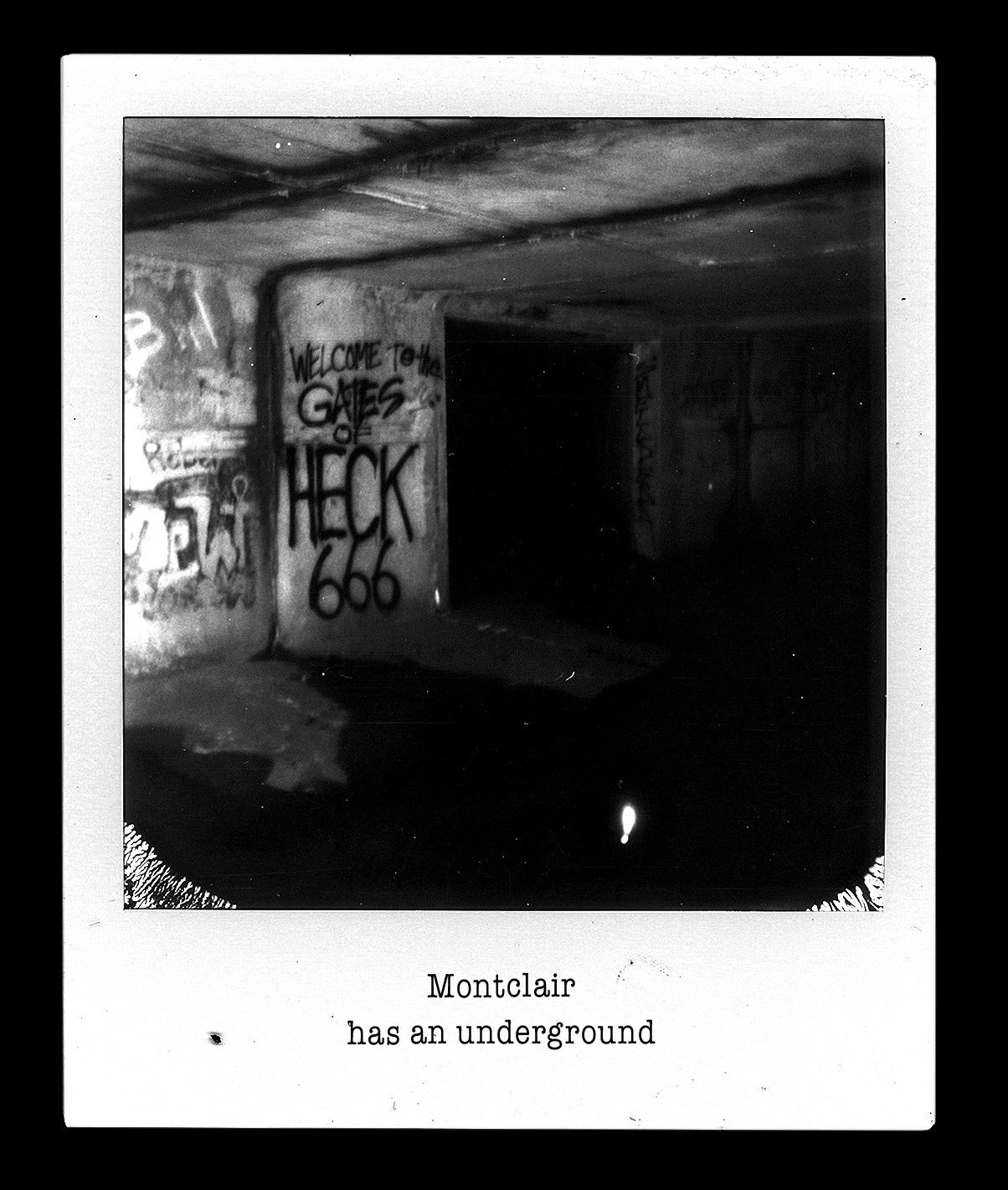

Once again, stay-at-home isolation lit a creative fire inside him. Turning to his using remedy – a concoction of danger and adventure – the first place Antabanez went to shoot was the so-called Gates of Heck, a murky underground tunnel system in Montclair.

“I needed to do something to feel alive –so I brought myself into the deepest, darkest pit of Montclair,” he said.

Although he usually shoots with a digital camera, Antabanez said he began experimenting with Polaroids after hearing about André Bosman and his personal crusade to save Polaroid film, following the company’s announcement to close its factory in the Netherlands.

“I was following this whole saga because as a photographer, it really fascinated me,” he said.

The quality of the photographs is remarkable – Polaroid photographs are not associated with high resolution, perhaps because those who grew up in the 80s and 90s often used them indoors under the harsh light of the flash.

“It’s a challenging format,” he said. “The film needs a lot of light.”

The film lends his image a dream–like quality, fitting given the subject of his photos, which evoke a suspenseful, eerie atmosphere in cemeteries, tunnels, and abandoned warehouses.

While Antabanez often gravitates toward macabre subjects, the message underlying his work is quite inspirational – when life is starting to get you down, maybe what you need is a good scare to get the blood flowing.